There’s a room at SAM where I lost track of time, and I’m still not entirely sure what happened to me there.

Pierre Huyghe’s Offspring is an AI-controlled installation that orchestrates light, smoke, and sound in response to environmental shifts and visitor movement. It’s constantly changing, never the same twice, a ballet without actors. For a few minutes, I was completely mesmerized, a captive audience to something that didn’t care whether I was watching or not. The smoke curled. The lights shifted. The music (infinite variations on Erik Satie’s Gymnopédies) drifted through the space like it was lost and didn’t mind.

That’s the thing about self-generating systems: you can never really see them completely. Every time I walked back into that room, the composition had shifted. Different lights. Different density of smoke. A slightly altered musical phrase hanging in the air. It was like the piece was having a conversation with itself, and I just happened to be eavesdropping.

There’s something almost hypnotic about watching a system make decisions without you. It reminded me of staring at waves, or a fire, those natural phenomena that hold your attention through pure variation and rhythm. Except this wasn’t natural. It was deeply artificial, and somehow that made it more fascinating. Here was technology performing its own version of aliveness, indifferent to whether anyone was watching, generating moments of beauty that would never repeat.

I lost myself there. Not in a transcendent way, but in the way you lose yourself when you’re watching something that doesn’t need you but somehow makes space for you anyway.

I felt mesmerized, even a little cold. And I couldn’t look away.

This is how Singapore Biennale 2025 works. It doesn’t announce itself with marble and reverence. It just quietly pulls you into encounters you didn’t see coming.

The thing about SAM at Tanjong Pagar Distripark is that it already feels like art before you encounter any art. It’s a former warehouse in an industrial port area, all concrete bones and utilitarian beauty, the kind of space that makes you hyper-aware of scale and echo. The Biennale’s theme is “pure intention,” which is one of those prompts that sounds profound until you think about it too hard, and then it just sounds impossible. What does it mean to have pure intention in a city built on carefully calibrated efficiency? In a port designed to move things faster than you can think about them? In an art context where everything has been filtered through curatorial frameworks and institutional approvals?

SAM doesn’t try to answer this. Instead, it offers you encounters, sometimes gentle, sometimes confrontational, with objects and environments that suggest intention is never really pure. It’s always metabolizing something else.

The inflatable people are breathing wrong, and I love them for it.

Paul Chan’s Khara En Tria (Joyer in 3) lives in the reception foyer, three brightly colored nylon figures powered by electric fans, inflating and deflating in distinct, slightly asynchronous rhythms. They’re supposed to evoke the classical figure of the bather, that art history staple where naked people lounge around being symbolic of nature and pleasure and the ideal body. But Chan’s bathers are not lounging. They’re flailing, swaying, collapsing, reviving. They look ecstatic and futile at the same time, like they can’t decide if they’re celebrating or surrendering.

The piece is called “breathing artworks,” inspired by philosophical traditions that connect breath and spirit, but honestly? They just feel alive in the most chaotic, human way. One seems joyful. One seems desperate. One seems like it’s having an okay time but wouldn’t mind if you turned off the fan. I watched a kid try to hug one, which the museum staff gently discouraged, and I completely understood the impulse. They make you want to touch them, to confirm they’re not actually breathing on their own.

This is what good art does in an industrial space: it makes the sterile feel intimate, the abstract feel embodied. These figures are awkward and gorgeous, and they refuse to settle into a single emotion, which feels about right for 2025.

Gallery 1 is where things get complicated, this is also where you can find Pierre Huyghe’s Offspring.

This is the big room, the sprawling one, and it’s been arranged like a slow-burn conversation between the past and a future that hasn’t decided what it wants to be yet. Works from Singapore’s National Collection sit alongside new commissions, and the whole space hums with this low-level tension between disaster and progress, absence and presence, the biological and the bureaucratic.

Álvaro Urbano’s Garden City (Orchidaceae) offers a warmer kind of strange. He’s populated the gallery with sculptural plants, fake orchids and cash crops rendered entirely in stainless steel, their metallic forms catching and reflecting the shifting light from Huyghe’s piece. The work references 19th-century botanical illustrations commissioned by British colonial officer William Farquhar, and it layers that history with Singapore’s modern use of orchids as diplomatic gifts, a tool of soft power dressed up as nature.

The plants are gorgeous and deeply unsettling. They look almost alive until you get close enough to see they’re not, and then they look like the kind of life you’d engineer if you’d forgotten what wildness felt like. Which is, of course, the point. Urbano is playing with the tension between Singapore’s manicured green spaces and the actual, uncontrollable verdancy of the tropics. His plants are utopian and dystopian at once: perfect, legible, and fundamentally dead.

I kept thinking about the word “cultivate” and how it contains both care and control.

Cui Jie’s Thermal Landscapes is a painting, which feels almost quaint in a room dominated by video and sensors and algorithmic compositions, but it holds its ground. The work is massive, inspired by Singapore’s watchtowers, those modernist structures that were supposed to showcase the city’s rapid development, offering vantage points to see progress in real time. In Cui’s painting, these architectural icons blend into statues of human and animal forms, which in turn resemble kitsch ceramic figurines from the mid-20th century, the kind of sentimental decorative objects your grandma might have collected.

The whole composition floats in a vast ocean, connected by a network of undersea cables, punctuated by diminished motifs of land. It’s a metaphor for ideology as infrastructure, for the way ideas flow invisibly beneath the surface, shaping both the built environment and the natural one. But it’s also just a weird, compelling image: lonely and crowded at the same time, nostalgic and futuristic, like someone painted a memory of the future that never quite arrived.

Ju Young Kim’s Aeroplastics series makes me want to fly somewhere and cry.

She’s taken components from commercial aircraft, those generic, deliberately characterless interiors designed to move bodies efficiently through space, and infused them with deeply personal, almost romantic elements. Where the tide carries us features an actual aircraft window fitted with stained glass, showing a staircase descending into the Venetian lagoon. It’s Art Nouveau meeting aerospace engineering, desire meeting displacement, the private life of an unknown passenger projected onto the most impersonal design imaginable.

There’s something unbearably tender about these works. Kim is insisting that transit spaces (airports, airplanes, the liminal zones of global mobility) are not neutral. They’re full of longing, memory, aspiration, grief. They’re full of people who are going somewhere they desperately want to be, or somewhere they desperately don’t want to leave, or somewhere they’ve convinced themselves will fix everything that feels broken.

I’ve never looked at an airplane window the same way twice.

Ming Wong’s Filem-Filem-Filem is quieter, but it accumulates power the longer you look. It’s a series of 50 instant photographs documenting abandoned or repurposed cinemas across Singapore and Malaysia, those mid-century “dream palaces” built in Art Deco and Bauhaus styles, now silent witnesses to a vanished era of communal film-watching. Wong presents them as Polaroids, which gives them a sense of intimacy and immediacy, except they’re not actually Polaroids. He’s digitally composited and re-photographed each image, creating what he calls “an unreal architectural presence.”

The cinemas look like ghosts. Some have been converted into shopping centers or storage facilities. Some are just there, empty and waiting. They capture that specific melancholy of infrastructure that outlives its purpose. The building remains, but the life inside it has moved on.

I grew up going to multiplex cinemas in suburban shopping malls, and even those feel nostalgic now, so looking at Wong’s photographs felt like looking at the fossils of my own future nostalgia. Which is maybe the most 2025 feeling there is.

There’s a shipping container outside the museum, and it’s full of sambal.

Well, not just sambal. Also crackers, perfume, mystery boxes that might contain literally anything. 400 boxes total, the kind that travel weekly from Batam to Singapore, the mundane miracle of transnational trade reduced to its most honest form: stuff people actually want. CAMP, an artist collective from India, has turned this 20-foot steel box into what they’re calling a “metabolic container,” which is a fancy way of saying they’ve made logistics feel like a living thing. You enter alone (one person at a time, like a confessional), and inside, the boxes are arranged not by category or destination but by something weirder, a diffusion-inspired flow borrowed from image generation algorithms. Boxes meet their neighbors. Features get sampled. Noise enters the system. New combinations emerge.

Here’s the thing about SAM that I keep coming back to: it feels like the emotional anchor of the entire Biennale, even though most of the exhibition is scattered across the city.

Maybe it’s the intimacy of the space, despite its industrial scale. Maybe it’s the way the works here deal so directly with the physical stuff of life: bodies, food, buildings, the objects we carry across borders, the memories we can’t quite let go of. Maybe it’s just that the port setting makes everything feel connected to movement, to the global flows of goods and people and ideas that Singapore has turned into a national identity.

Or maybe it’s simpler than that. Maybe SAM just knows how to make absence feel present.

So many of these works are about what’s not there anymore: the cinemas that closed, the natural wildness that got landscaped away, the passengers whose desires never made it into the airplane’s design brief, the traditions that are disappearing faster than we can document them. But they’re not mourning, exactly. They’re just noticing. Paying attention. Suggesting that attention itself might be a kind of intention, even if it’s never pure.

I left through the reception foyer, past Paul Chan’s inflatable bathers still flailing away, and stepped back into the port district with its cranes and containers and the efficient choreography of global trade. But I kept thinking about Huyghe’s Offspring, that self-generating system still running in Gallery 1, still making decisions, still producing moments that no one would ever see exactly the same way again.

And I thought: this is what good art does. It doesn’t give you answers. It just quietly rearranges your inner furniture, shifts things a few inches to the left, and leaves you standing in a slightly different relationship to the world than you were before.

Offspring held me captive for those few minutes not because it demanded my attention, but because it was so thoroughly absorbed in its own process. It was a machine making art for itself, and I just happened to be there to witness it. That feeling of watching something alive that doesn’t need you but allows you to be present anyway, that’s the thing I’ll carry with me.

Pure intention is impossible, but maybe attention to the whole messy metabolic process of living together on a planet full of self-generating systems (some natural, some artificial, all equally indifferent and beautiful) is enough.

BONUS: When Objects Won’t Stop Talking: SAM’s New Collection Shows and the Art That Refuses to Sit Still

There’s a bed hanging from the ceiling, and it’s bleeding.

Well, not bleeding exactly. But Suzann Victor’s Third World Extra Virgin Dreams is draped with a ten-meter tapestry of glass lenses, each one holding a brush of human blood, and the whole thing hovers above you like some kind of gorgeous, terrifying benediction. It’s in Gallery 4 at SAM, part of Talking Objects, and it’s the kind of work that makes you realize objects are never really neutral. They’re always carrying something, memory, violence, desire, the imprint of every body that’s touched them.

This is the thesis of SAM’s two new collection exhibitions, which opened in September and run through July 2026. Talking Objects and The Living Room are companion shows, both in Gallery 4, both free for Singaporeans, both asking versions of the same impossible question: How do you hold onto art when art refuses to be held?

Objects with opinions

Talking Objects is the more straightforward of the two, if you can call anything straightforward when it includes a seven-meter-tall cascade of stainless steel pots and pans that’s somehow both a monument to Indian industrialization and a critique of how we mistake ubiquity for equality. That’s Subodh Gupta’s Hungry God, and it gleams like an offering to a deity that’s never satisfied, which is, of course, exactly the point.

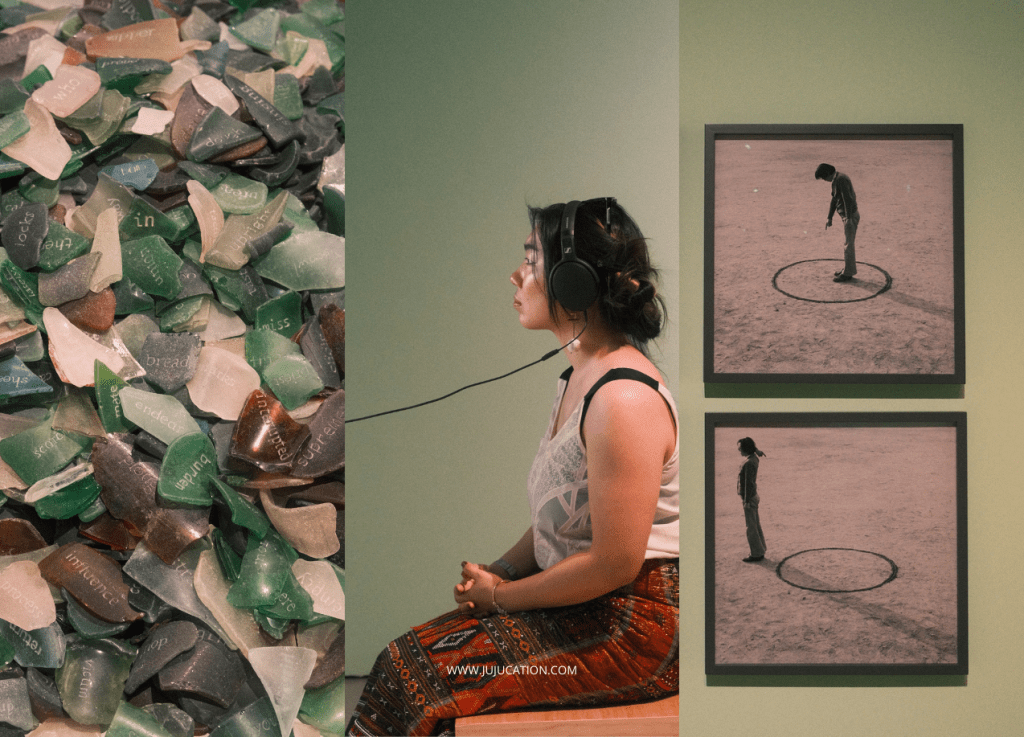

The exhibition brings together works from SAM’s collection that explore how everyday items and familiar representations accumulate meaning through use, circulation, and the artist’s transforming touch. It’s about slowing down. Looking harder. Recognizing that a typewriter isn’t just a typewriter when Christine Ay Tjoe strips it to its bones, suspends it from wires, and turns eighteen keys into long arms reaching desperately outward while a haunting musical composition plays in the background. Press certain key combinations and the music changes. You’re not just viewing the work, you’re completing it, adding your own emotional fingerprints to what’s already there.

Alwin Reamillo’s reconstructed grand piano hits me differently every time I think about it. Made from the remnants of his late father’s defunct piano workshop in the Philippines, once the only maker of grand pianos in the country until cheap factory models put them out of business, the instrument is both memorial and “social sculpture.” Reamillo invited the craftsmen who used to work with his father to help rebuild it. Now visitors can play it, extending its life, its legacy, its purpose beyond what any single person intended.

There’s something unbearably tender about how these objects refuse to stay in the past tense.

Simryn Gill collected seawashed glass from Malaysian and Singaporean beaches and engraved words onto each fragment. You can’t tell what these objects used to be, bottles? windows? something else entirely? and their histories are unknowable. But Gill has given them new language, invited you to bring your own meanings, turned erosion into a kind of poetry. The work is called Washed Up, which is funny in a dark way, because these fragments are anything but finished. They’re still talking.

The room where performance goes to live

The Living Room is harder to pin down, which is appropriate for an exhibition about performance art, that most ephemeral of forms, the one that vanishes as it happens and leaves behind only traces, questions, maybe a bit of chaos.

The show brings together performance-based works from SAM, Seoul Museum of Art, and Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, alongside invited artists. It’s the final chapter of a three-part collaboration exploring how museums might collect, care for, and re-present practices that were never meant to be preserved.

Chia Chuyia’s Knitting the Future is the emotional centerpiece. In 2016, she sat inside a glass gallery for five weeks, six days a week, six hours a day, knitting a full-length garment from bright green strands of leek. She called it “body armor,” a gesture of protection for the body and the land that sustains it. On the final day, she wore it proudly and offered it to the crowd outside.

The garment entered SAM’s collection along with video documentation. But leeks aren’t meant to last forever. Over the years in storage, the vivid greens and yellows have darkened to brown and black. The garment has become increasingly fragile, resisting every effort to keep it unchanged.

So what do you do with a work that’s actively dying?

During Singapore Art Week in January 2026, Chia will return to perform a closing ritual, a final activation that tends to the garment’s last moments and lays it to rest. The work asks: What does it mean to care for art even as you prepare to let it go?

I can’t stop thinking about this. About how museums are supposed to preserve things forever, but some things aren’t meant to be forever. Some things are meant to grow, change, darken, crumble. And maybe care looks different when you’re not trying to stop time.

Ezzam Rahman is revisiting his 2015 performance Allow Me to Introduce Myself, now retitled Allow Me to Reintroduce Myself. The original involved talcum powder, breath, second-hand furniture, glass jars, and the artist dressed head to toe in white. He inhaled powder and exhaled it in soft clouds. Sometimes he coughed, the powder catching in his throat, refusing to be only symbolic.

Nearly a decade later, he’s meeting this work again, but his body has aged. His relationship to performance has evolved. This isn’t a reenactment, it’s a renewed encounter, shaped by everything that’s happened in between.

How do you carry your past selves? What happens when you meet yourself again ten years later and realize you’ve both changed?

Jeremy Hiah’s Performance Journal Scroll unfurls across ten meters of paper, a hand-drawn map of two decades of performance art rendered in charcoal. Unlike photographs that freeze a moment, drawing lets memory flow, mixing what was seen with what was felt, imagined, remembered differently. Strange creatures wander across the scroll alongside figures from his past performances. It’s journal and dreamscape at once, autobiography and fiction tangled together until you can’t tell where one ends and the other begins.

The scroll is accompanied by The Albino Circus, nearly an hour of video and photo montage showing performances in galleries, public spaces, and Hiah’s own living room, because performance doesn’t need a stage. It just needs bodies and attention and willingness to let something happen.

The participatory works are where things get interesting

Kim Ga Ram’s The AGENDA Hair Salon will be reactivated during Singapore Art Week. She’s a trained hairdresser, and she offers free haircuts in exchange for conversation. You choose a cutting cape printed with a slogan about a social issue. Then you decide how much hair to part with. The more committed you feel to the cause, the more hair you give, anywhere from a trim to a full shave.

It’s absurd and earnest at the same time, turning vanity into vulnerability, turning the everyday ritual of getting your hair cut into a public declaration of values. How much of yourself are you willing to sacrifice for what you believe in? A strand? A lock? All of it?

Nam Hwayeon’s Ehera Noara reconstructs a 1933 performance by pioneering Korean dancer Choi Seung-hee that survives only through a few photographs and written accounts. Working from these fragments, Nam filled in the missing moments, creating a living archive that will be performed daily during Art Week. The work will later be entrusted to appointed custodians, ensuring it continues moving across bodies, generations, time.

When only fragments remain, what do you preserve and what do you reinvent? How do these gestures change in your hands?

Here’s what gets me about these exhibitions

They’re both interrogating the same fundamental tension: Museums want to collect things, but some art resists collection. Some art is meant to change, decay, disappear. Some art only exists in the doing of it, in the encounter between bodies in a specific moment that can never be exactly repeated.

Talking Objects says: Look, even solid things, beds, typewriters, pianos, kitchen utensils, are never really stable. They’re always accumulating meanings, carrying histories, transforming through use and attention and the stories we tell about them.

The Living Room says: Okay, but what about art that was never solid to begin with? Art that exists only as action, breath, gesture, duration? How do you care for the ephemeral? How do you preserve what was designed to vanish?

Neither exhibition offers easy answers, which is what makes them worth spending time with. They’re asking questions that museums have been wrestling with for decades, but they’re asking them with such specificity, such attention to individual works and artists and materials, that the questions feel new.

I keep coming back to Victor’s suspended bed with its tapestry of blood-filled lenses. It’s been in SAM’s collection since 1997 (remade in 2010), and it’s still absolutely uncompromising. The bed is where life begins and ends, where we’re most vulnerable, most ourselves. The lenses refract light, creating a dreamlike state between fragility and strength, visibility and invisibility.

And the blood, mixed from multiple donors, according to the artist, turns the whole thing into a quilt of subjectivities, a patchwork of lives in their most vulnerable manifestation.

Objects talk, but they don’t always say what we expect them to say. Sometimes they whisper. Sometimes they scream. Sometimes they just sit there holding space for everything we can’t articulate, all the mess and beauty and contradiction of being alive in a body, in a place, in a specific moment of history that’s already becoming memory as it happens.

I left Gallery 4 thinking about care, not the sentimental kind, but the difficult kind. The kind that knows when to hold on and when to let go. The kind that honors transformation instead of fighting it. The kind that asks what art needs from us, rather than assuming we know.

Both exhibitions run through July 2026, which means they’ll outlast the Biennale by several months. They’ll be there through Singapore’s seasons (all two of them: hot and slightly less hot), through countless school groups and tourist visits and quiet weekday afternoons when the gallery is nearly empty and you can stand in front of a work for as long as you want without anyone hurrying you along.

Go see them. Go more than once. Let the objects talk to you. Let the performances haunt you even in their absence. Bring your own meanings. Leave changed.

And if you make it to Singapore Art Week in January, go get your hair cut at Kim Ga Ram’s salon. Choose a cape. Decide how much you’re willing to give. Sit in that temporary, participatory space where art and life blur together and remember: nothing stays the same forever, and maybe that’s exactly as it should be.

The leek garment is dying, and in January, we’ll gather to say goodbye. What could be more human than that?