Content warnings include suicide (central to plot), panic attacks, grief, and family trauma. Skip if these are triggers.

I need to be honest with you about something: I’m tired of books that treat trauma like a personality quirk that evaporates the moment someone hot pays attention to you. You know the ones. “She was broken until HE showed her how to live again!” As if depression is just waiting for the right meet-cute to pack its bags.

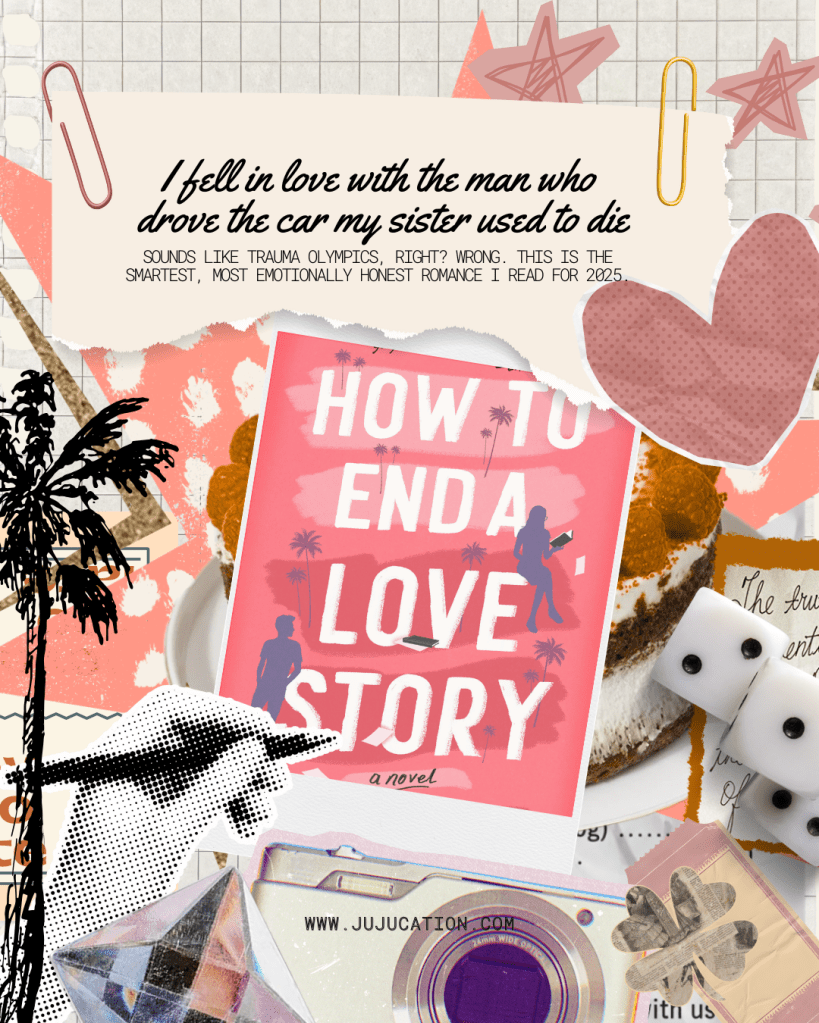

So when I picked up Yulin Kuang’s How to End a Love Story, I was prepared to be annoyed. The premise alone sounds like it was engineered in a laboratory to make me cry and then argue with strangers on the internet about whether it’s “problematic.” Spoiler: it’s not. It’s perfect. And yes, I cried. Twice. Once during a craft project I’ll tell you about later.

The Setup (Or: How to Ruin a Writers’ Room in One Easy Step)

Helen Zhang is living her best life. Bestselling YA author. Television adaptation greenlit. Writers’ room position secured. Los Angeles sunshine. The dream, right?

Then Grant Shepard walks in.

Grant Shepard, whose car was used by Helen’s sister Michelle to end her life thirteen years ago. Grant Shepard, who became the convenient villain in a tragedy that had no villains, only victims. Grant Shepard, who Helen’s family blamed because blame needs somewhere to land and grief doesn’t come with an instruction manual.

Now they’re coworkers. Now they have to sit in the same room and pretend the past isn’t sitting between them like an uninvited guest who won’t stop talking.

If you’re thinking “this sounds deeply uncomfortable,” you’re correct. If you’re also thinking “I need to read this immediately,” you’re also correct.

What This Book Actually Understands (That Most Don’t)

Here’s what Yulin Kuang gets that so many writers miss: trauma doesn’t make you interesting. It makes you tired. It makes you perform normalcy until you’re so good at the performance you forget what genuine emotion feels like. It makes you successful and hollow simultaneously, which is a special kind of hell that looks great on Instagram.

Both Helen and Grant are drowning in their own ways. Helen in expectations and unprocessed sibling grief. Grant in panic attacks and the exhausting work of proving he deserves to exist. They’re not broken people who need fixing. They’re functional people who are slowly realizing that “functional” and “healed” are not the same thing.

The romance doesn’t fix them. Let me say that again for the people in the back: THE ROMANCE DOESN’T FIX THEM. Instead, it creates a space where they can stop pretending. Where panic attacks can happen without shame. Where grief can be named instead of swallowed.

That’s the radical part. Not the falling in love. The permission to fall apart first.

8 Things This Book Taught Me (While Making Me Feel Feelings)

1. Scapegoating Is Grief’s Favorite Coping Mechanism Helen’s family needed someone to blame. Grant was there. It wasn’t fair, but fairness doesn’t factor into survival mode. We’ve all done some version of this, blaming the messenger instead of confronting the unbearable message.

2. Your Body Keeps the Score (Even When Your Mind Pretends It’s Fine) Grant’s panic attacks are triggered by loss of control, especially in cars. Thirteen years later, his body still remembers what his mind tries to forget. Your anxiety isn’t irrational. It’s information.

3. The Last Conversation Haunts Forever Helen and Michelle fought about a necklace. Something so small it should be forgettable. Except it wasn’t the last conversation, it was THE last conversation. This will change how you end phone calls with people you love.

4. Success Without Healing Is Interior Decorating an Empty House Both characters are professionally successful. Helen is a bestselling author. Grant is respected in Hollywood. Neither feels whole. Achievements can’t fill the holes grief leaves behind.

5. Performative Wellness Is Exhausting They both look fine. Great, even. They’ve mastered the art of seeming okay. But “seeming” is labor, and eventually, you run out of energy for the performance.

6. Chosen Family Saves Lives The writers’ room becomes their safe space. Not because it’s perfect, but because these people choose to show up. Blood doesn’t make family. Intention does.

7. Vulnerability Is Scarier Than Sex The steamiest scene in this book? When Grant tells Helen about his panic attacks. When Helen admits she can’t feel her own feelings. That’s the real intimacy. Everything else is just bodies.

8. Forgiveness Is About Release, Not Absolution Helen doesn’t forgive Grant because he was guilty. She forgives him because holding onto blame was destroying her. Forgiveness is ultimately selfish in the best possible way. It’s choosing your own peace.

The Craft Project: Writing My Own Grief Letter

Helen writes letters to Michelle throughout the book. Unsent. Unread. But necessary.

I decided to write my own. To my uncle, Atcheng, who died earlier this year. My childhood hero, father figure, the person who understood me before I understood myself.

Materials I Used:

- Quality stationery (the kind that feels important)

- My favorite pen, a Sailor Fountain pen in Cherry Blossoms at Night

- His favorite playlist

- Tissues (not optional)

- One hour of uninterrupted time

The Process:

- I set up a space that felt sacred. Queued his music.

- I wrote “Dear Atcheng” (the nickname I gave him when I was young) at the top and just started.

- I didn’t edit. Didn’t censor. Let myself say everything I couldn’t say at the funeral.

- I cried. Laughed. Remembered specific conversations. Admitted how much I still miss him.

- I sealed the letter. I didn’t need to send it. Writing it was the point.

This isn’t about him reading it (though who knows, maybe he does). This is about giving yourself permission to say the unsayable. To process what you’ve been holding. To stop performing and start feeling.

Helen’s letters save her. Mine didn’t save me, but they reminded me I’m still here. Still missing him. Still allowed to grieve even when the world expects me to be “over it.”

Try this: Write your own letter. To someone you lost. Someone who hurt you. A version of yourself you had to leave behind. You don’t have to share it. You don’t even have to keep it. But write it. See what happens when you stop holding everything in.

Who This Book Is For (And Who Should Run)

Read this if:

- You’re tired of romance that treats mental health like a plot device

- You’ve ever felt successful and empty simultaneously

- You’re in your thirties and exhausted by books about 22-year-olds discovering emotions

- You need proof that shared trauma can become shared healing

- You have a therapist and a sense of humor about your own dysfunction

- You’re an Emily Henry fan who wants something with sharper edges

Skip this if:

- You want light and fluffy (this is neither)

- Suicide is a significant trigger (it’s central and detailed)

- You prefer instalove to slow-burn emotional excavation

- You think love should solve all problems instantly

- You’re looking for action and external plot stakes

- You need everyone healed and perfect by the final page

The Verdict

How to End a Love Story is what happens when a talented screenwriter (yes, Yulin Kuang adapted Emily Henry’s Beach Read) decides to write her own trauma-informed romance. It’s smart. It’s honest. It refuses to offer easy answers because easy answers don’t exist for hard questions.

This isn’t a book about grief. It’s a book about what happens after grief, when you realize you’ve been performing wholeness for so long you’ve forgotten what actual healing looks like. When you meet someone who’s been performing the same show, and suddenly neither of you has to pretend anymore.

Helen and Grant don’t get a traditional happily ever after. They get something better: a tentatively hopeful, deliberately chosen, “let’s try this and see what happens” beginning. With therapy. And continued panic attacks. And complicated families. And each other.

Sometimes that’s the most radical happy ending of all.

Rating: 4.0/5 stars (half point deducted because I needed MORE and that’s not fair but it’s true)

Final thoughts: Read this book. Write your grief letter. Call someone you love. In that order.

READY TO DISCUSS? Drop a comment below telling me: What’s the last book that made you feel uncomfortably seen? Or if you’ve written your own grief letter, how did it feel? Let’s process our feelings together like the well-adjusted adults we’re pretending to be.